A study on Neo4j's pagecache

As my course project for CS848 Graph Analytics and Data Management in my last term at the University of Waterloo, I did an empirical study on the page cache component of Neo4j, an open-source graph database system. Here is a somewhat lengthy blog post about it :)

Table of Content

- GClock

- LRU, Friends, or Foes?

- Making LRU More Performant

- Experiment

- Results

- Ending

- Changelog

- Footnote

GClock

I was interested in the impact of different cache replacement policies on the performance of the database. At the time, Neo4j (3.5.14.0) used the GClock algorithm to select a page to evict when the page cache runs out of space. GClock is a simple algorithm that keeps a counter on each buffer page as an approximate measure for the frequency of access of the page. When there is a need to evict a page, the algorithm scans the list of pages sequentially, decreases the counter value of the page by 1, and evicts the page if the counter reaches 0. If the counter is non-zero after the decrement, the algorithm moves on to the next page and repeats until a “victim”, a page with a counter value of 0, is found. When a victim page is found, the algorithm records the position of the page, evict the page by flushing any dirty content of the page onto the disk, and returns an empty page to the caller. The position of the victim page is used as the starting position of the next scan. Because of this recording, the page just returned to the caller will not be evicted until at least another full scan of the page cache. Finally, whenever a page is accessed, its counter is incremented by 1, bounded by a user-specified maximum value. This is the gist of the replacement algorithm. Of course, when integrating with a database, we need to make some small changes to tailor to the needs of the database application logic. For example, a running transaction of the database can “pin” a page to signal to the cache replacement algorithm that the page should not be evicted.

LRU, Friends, or Foes?

Curious by the choice of GClock in Neo4j, I wonder why more well-known algorithms like LRU was not used. So I wanted to do a study to evaluate the performances of the different algorithms. The algorithms I initially selected are:

Random- select a page uniformly randomly and evict that pageLRU- evict the page that was used least recentlyS4LRU- organize the pages into 4LRUlistsL1,L2,L3, andL4. The level of the list represents the “hotness” of the pages that are in the list. SoL4stores pages that have been most “hot” and probably should not be evicted first. Similarly,L1stores pages that are least “hot” and eviction starts from the tail of theL1list. When a page at levelkis accessed, it is either moved to the head of the list or promoted to the levelk+1list if it is already at the front of the list.

As I implement the LRU-based algorithms, I found one potential reason why GClock was preferred over the LRU variants: most LRU-based algorithms maintain a doubly-linked list to implement the “least-recently-used” policy. When a page is accessed, the page’s id is used to look up the linked list node representing the page via a hash table. After the node is found, it is moved to the head of the list. This “moving the node to the head of the list” operation becomes problematic in a multi-threaded environment. To make the data structure thread-safe, the thread needs to take an exclusive lock, thereby serializing all threads behind a single lock [1]. One simple way to reduce the contention is to shard the pages into multiple lists, which is what S4LRU does. Even then, we can see that thread contention can still be a bottleneck of the algorithm. In comparison, the GClock algorithm only requires maintaining a counter on each page. Thread safety can be ensured by using an atomic counter. As for the Random algorithm, there is no maintenance needed at all! From this perspective, we can see that GClock and Random are more scalable than the LRU-based algorithms.

Making LRU More Performant

Having identified this problem, I began looking into the academic literature for ways to optimize the LRU algorithms. I found two interesting techniques that people have devised to solve/alleviate this problem:

- Batching - I found this technique from a paper titled “BP-Wrapper: A System Framework Making Any Replacement Algorithms (Almost) Lock Contention Free”. The batching technique relies on the observation that the LRU list maintenance does not have to be performed after every operation. For example, if two reads of pages all hit pages that are already in the page cache, then no eviction decision needs to be made and these two reads can be batched together to update the LRU list only once.

- Flat combining - this technique is from a paper titled “Flat combining and the synchronization-parallelism tradeoff”. The idea of the technique is to batch operations from multiple threads together and have one thread perform all the operations on behalf of the other threads. This might seem strange at first thought since we effectively have only one thread that is doing real work. But the paper argues that for data structures that have a few serialization bottlenecks it is better to reduce contention by having one thread do all the work and show good performance when using this technique for those data structures.

On a high-level, technique #1 can be thought of as performing batching within a thread, and technique #2 can be thought of as performing batching across threads. The ConcurrentLinkedHashMap (also used in Guava’s cache) is such an implementation that combines both techniques. I adapted this implementation into Neo4j and call this algorithm ConcurrentLinkedHashMapLRU.

Experiment

To evaluate the performance of all the algorithms mentioned above, I conducted an experiment using the LDBC Social Network SF10 datasets. This dataset simulates an artificial social network and contains 65645 PERSON nodes and 1938516 KNOWS edges. A common workload in a graph database system is to retrieve the size of a user’s social network, i.e., for a given user A, count the number of users who are friends with A, who are friends with friends of A, and so on. This can be done by issuing the following Cypher query to Neo4j

MATCH (person: Person {id:$personId})-[path:KNOWS*1..3]-(friend:Person)

RETURN COUNT(distinct friend)

In this case, I defined the size of a user’s social network to include all friends reachable in 3 hops. Then I randomly selected 320 users in the dataset as the source ($personId) of the query [2]. To make sure that eviction happens, I set the size of the cache to be smaller (16MB and 32MB) than the resident size of caching all the data. As for metrics, I collected throughput (txn/s), transaction latency (ms), and hit ratio (broken down by the type of pages). Finally, the experiment is run for all the algorithms for different numbers of threads.

Results

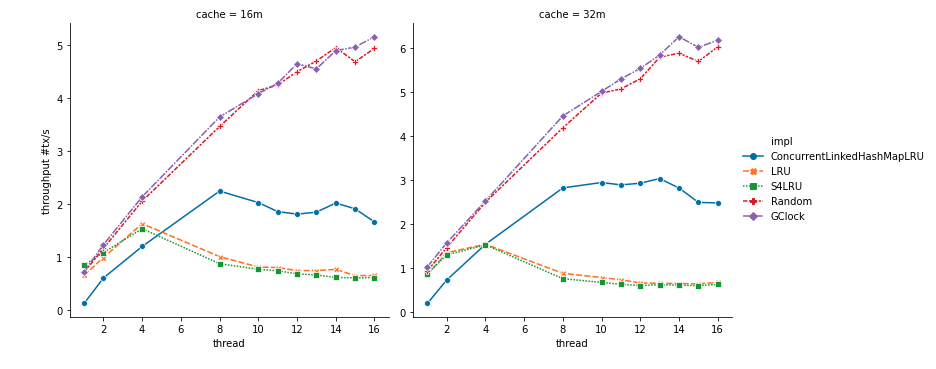

The figure below shows the system throughput on the Y-axis and the number of threads on the X-axis. Here are some observations:

- As we can see, both

RandomandGClockscale linearly as the number of threads increases. - As expected,

LRUandS4LRUfailed to scale beyond 4 threads and performances started to degrade as more threads are used. ConcurrentLinkedHashMapLRUwas worse than all algorithms for 1 thread due to the overhead of implementing batching and flat combining. However, it did scale to about 8 threads and was much better thanLRUandS4LRU.

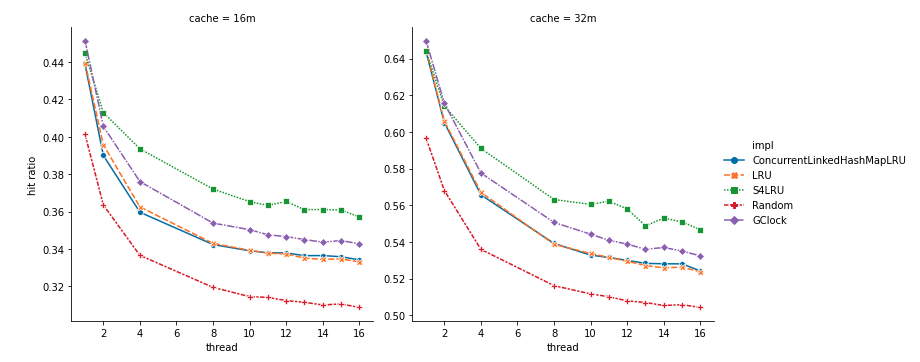

Throughput can be affected by both the scalability of the algorithm but also the effectiveness of the algorithm in retaining important pages and evicting less important ones. The figure below shows the hit ratio of the cache on the Y-axis and the number of threads on the X-axis. As we can see, GClock has a similar performance as the LRU-based algorithms. Although Random is consistently worse than the rest of the algorithms, it is not too far off. This can explain why the throughput of Random is very close to that of GClock in the figure above.

Ending

In this empirical study, I learned that simple cache replacement algorithms like Random and GClock can yield higher overall system performance than more sophisticated ones due to concurrency gains, despite yielding similar or worse hit ratio. Although it goes without saying that these results are specific to the databases, the workloads, and many more factors, I think this teaches us a great lesson about the beauty and power of simplicity.

I have left out many details of the study and the project to avoid making this blog post too long. If you are interested in learning more about the study, feel free to reach out to me and I am more than happy to share more and discuss databases!

Changelog

2021-06-26 updates

I recently learned that the version of Neo4j (3.5.14.0) used in my experiment did not make use of the direct I/O support (ExtendedOptions.DIRECT) available in the JDK. The support was added to Neo4j 4.X version in this commit. This means that all the data in the experiment that was supposed to be loaded from disk to the database buffer directly was probably loaded from the file system page cache (the cache has been warmed during the warmup period). This would give random and GClock unfair advantages because page load all of a sudden became much cheaper. This would explain why we observed much better hit ratio in LRU-based algorithms than random and GClock and yet random and GClock had much higher throughput. Oh well :(

Footnote

-

Note that there are other ways to implement this without using locks. For example, one can use more advanced primitives such as multi-word compare-and-swap to make the data structure lock-free. But still, the fundamental problem is that threads will contend at the head of the list. This problem will not magically vanish just because a lock-free implementation is used. Instead of threads waiting to acquire locks in a lock-based implementation, threads will likely be busy aborting the compare-and-swap operations. ↩

-

In this artificial dataset, the 3-hop query starting from most users typically reaches about 50,000 users, i.e., about 76% of all the users in the network. ↩